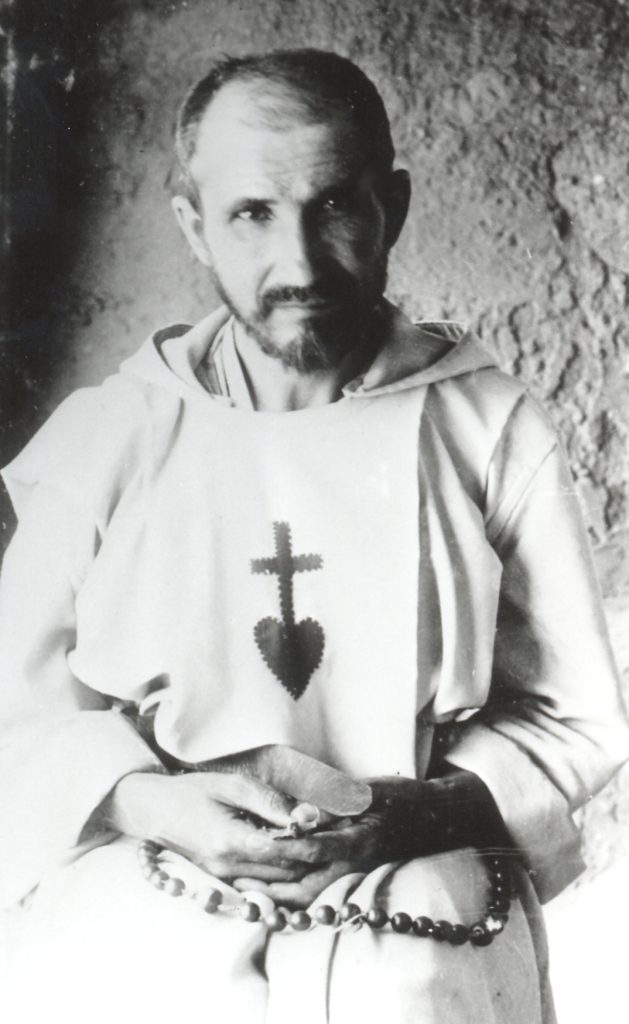

Charles de Foucauld was born in the mid 19th century into an old aristocratic French family. He spent the key years of his life in the Sahara desert as a Christian ‘monk’ among the local Tuareg people, who were followers of Islam. There he met his death in 1916, in the central Saharan oasis of Tamanrasset.

What, we can well ask, has he to say to us? We live in a world far removed from his, and our personal lives, whatever they may be, are surely quite unlike his. And yet, surprisingly, his life has had a profound influence on many today. People of all kinds have discovered through him ‘a word of life’ that gives meaning to their everyday lives, and a little sign of hope to encourage them on their journey.

The French society in which Charles was born and grew up was marked by strong, and often bitter, class distinctions. In theory the French revolution, with its famous slogan of ‘Freedom, Equality and Fraternity’, words inspired by the struggle for Independence in the USA, had abolished these distinctions. In fact the old feudal order, with its clear social hierarchy and its integration of Church and State, was replaced by new class divisions linked to the industrial revolution. The old feudal loyalties were replaced by the harsh economic laws of ‘hire and fire’: the worker became a ‘hired hand’, to be employed or laid aside, as needed.

This social context helps us to grasp the radical nature of Charles’ desire to imitate Jesus as the ‘workman of Nazareth’. Was not Jesus the ‘carpenter’? This, Charles reminds us, is a truth we had largely forgotten! And had he not chosen to be at the bottom of the social ladder, in ‘the lowest place’? Accompanying this industrialization, the western European powers engaged in a massive colonial expansion, especially in Africa. This led, inevitably, to an open or latent hostility between the new ‘rulers’, the colonizing military and civil authorities, and the ‘ruled’, the local peoples.

It was in this situation that Charles wished to be ‘the universal brother’, a brother to each and every person he encountered. Such a simple and bold claim strikes at the heart of inhuman structures and relationships, and begins to remake a world of respect and equality. Charles did this, not by words, he, as we do, mistrusted mere words, but by simple, everyday actions and gestures, with a readiness, when need be, to denounce abuses and take risks.

Work, especially manual work, was also looked down on by the Tuareg nobles. While few of us realize that the Sahara is even inhabited, the Tuareg, with whom Charles lived for over ten years, were a large but scattered group of nomadic peoples in the central Sahara, with an elaborate class structure. They have a rich and ancient culture and a deep faith, that of Islam. As Charles came to realize by sharing their life and studying their culture in detail, they looked down on the French occupants as ‘pagans’ and as ‘barbarians’. Most of the French, even if nominally Christian, did not express or practice their faith. The Tuareg saw them as people with superior force of arms and material, technological means but with no sense of authentic values such as hospitality, freedom and courage.

Reading Charles’ letters and personal reflections, we discover his own struggles to ‘see through’ the ingrained, largely unconscious opinions of national and religious superiority, and to begin to see the different, but equally real worth of the ‘other.’ As the French settlers came to bring ‘civilization’ and ‘Christianity’, so perhaps we in today’s West are tempted as neo-colonialists to offer, even impose, ‘free trade and democracy’ as well as our modern religion of ‘secular humanism.’ Let us allow Charles to challenge us! How sadly we deform the real values and truths that are ours, and close ourselves to the truth and goodness of those different from ourselves!

It is perhaps fortunate that Charles lost his Christian faith in adolescence. By rediscovering it through the living example of his Muslim hosts, in Morocco especially, he was not tempted to despise the profound value of their religion, nor its providential role in God’s plan. Returning to his Christian faith as a mature adult, he never doubted its God-given and absolute truth and he built his whole life, without reserve around it. The lived example of Brother Charles, totally faithful to Jesus, totally respectful of God’s ways in his neighbours, is surely a light for us today, particularly in relation to Islam and the Muslim people.

Charles as an adult had little, in fact almost no, experience of the ordinary life of the French Church of his day. Soon after his discovery of faith he became a monk and left for a poor monastery in Syria. But the religious picture in France was a complicated one. There were the ‘Jansenists’, who over-emphasized the judgment of God and the demand for ever stricter moral standards. There were the ‘Modernists’, who over emphasized the application of human reason, tending to interpret religion in terms of our developing human history and psychology. And then there were the ‘Skeptics’, those who denied the truth of any religious belief. Those who remained in the Church were influenced by their criticisms and doubts not unlike us in our own day. While these factors had played a role in Charles’ loss of faith as an adolescent, it seems as though once he found a genuine adult faith, he never allowed himself to be pulled into factional disputes but went to the ‘centre’ of faith, the person of Jesus. He went always to the ‘heart of the matter’, the unfathomable love of the one Source of all in the human life of Jesus, the man of Nazareth.

It must be added that the Catholic Church in France was also under attack at this time from the secular society. Many of its institutions had been closed, properties seized and most religious Orders were disbanded. The very presence of ‘missionaries’ in the colonies was barely tolerated.

This had an important effect on the ability of the Church to confront certain social structures both at home and abroad, not the least of which was the question of slavery. Although Charles’ military connections, as a former French officer and explorer, gave him a certain privileged access to the Saharan territories, he refused to be a ‘dumb sentinel’ but protested with vigour against the institution and practice of slavery.

On his return from exploring the interior of Morocco Charles wrote a book which became a best seller. If then he was known in his day as an ‘explorer’ we can also see that his whole life was an ‘exploration.’ Having discovered Jesus, he sought to discover who this Jesus really was. Visiting the little town of Nazareth, he suddenly became aware that Jesus had lived and worked in this ordinary, out-of-the-way place as a manual worker for some thirty years, in fact for all but three years of his life. If God became ‘one of us’, as he firmly believed, was it not extraordinary that God had chosen to enter our human history hi this apparently ‘insignificant’ way? A way that is ‘our’ way: the way that most of us live, the way of our common experience…

Charles explored and developed this insight for the rest of his life. It is the hidden ‘key’ that opens the door to our understanding of Charles’ life, and to the interest and importance of the ‘message’ that his life may have for each of us.

We can easily be absorbed by the dramatic and picturesque life of Charles as the intrepid explorer, risking his life, and then as the solitary ‘hermit in the Sahara.’ During this time of exploration he already wanted to get to know, understand and to be with the local people. On his return as a priest, he sought to found a ‘fraternity’, a community of brothers who would live his ideal of universal brotherhood. His conception of being a brother to one and all was not just a human ideal, but the lived consequence of Charles’ deep belief that God had come to share our life and to live as one of us, to be ‘our Brother.’

Our faith is so often separate from our daily life and choices. For Charles, to follow Jesus was to become ‘like Jesus,’ and to act like Jesus with every person and in every situation.

Of course we don’t, most of us, live in the desert! Nor do we live in Charles’ world or share his limited need of food and sleep, nor his almost boundless energy. But though him we can, each of us, whatever our situation, find inspiration, a ‘breath of the Spirit’, through him for our often empty lives.

Brother Charles leads us directly to Jesus, his constant Companion and Friend.